Medieval Cairo was one of the cities of "The Thousand and One Nights" and unlike Baghdad and Damascus many of its buildings from those times are still there, mostly hidden among the narrow streets and alleys of the old town. I spent many weekends searching them out to find some of them in terrible disrepair and others in remarkably good condition and still being used today. On this page I have included photos of just a few either because they are architecturally or historically notable. To show just how architectural rich Cairo really is below is a map of just part of the old city from Caroline Williams' excellent book "Islamic Monuments in Cairo"

From top to bottom is about 1.5kms

By Middle Eastern standards Cairo is actually rather young (the ancient Egyptian's capital, Memphis is a few kilometres to the south). It was founded during the Arab conquest in 641. Our earliest building, the mosque of Ibn Tulun was built 200 hundred years later in 876, but is important as it is the oldest intact functioning Islamic monument in Cairo and a rare example of the art and architecture of the classical period of Islam. The domed building seen in the courtyard is from a later restoration, but the minaret was inspired by the Great Mosque of Samarra which in turn was inspired from the ziggurats of Babylon.

Ibn Tulun's mosque was built during the Abbassid reign (750 - 935). However the mosque below, al-Azar, was built during the reign of the Fatimids who ruled the Islamic world from 969 -1171. It was built in 970 and is the oldest university in the world. It continues to play a dominant role today as the sheikh of al-Azar is the country's ultimate religious authority. It is still technically a university but most of its students are now taught at campuses off-site.

Although the central courtyard is original, it has been renovated many times and the minarets in the picture date from the 14th, 15th and 16th centuries.

One of the madder Fatimid Caliphs was al-Hakim. He was often to be found riding his donkey through the streets of Cairo and if he found any dishonest merchants cheating their customers he would have them sodomised by his large black servant who accompanied him for this purpose. He also banned women from appearing on the streets and to make sure they stayed indoors banned the making of women's shoes. He disappeared one night while riding his donkey and was never found. One of his followers thought this was proof of his divine nature and went on to preach in Syria and set up the Druze sect.

The mosque itself, built in 1010, has rarely been used as such. It was a prison for invading crusaders, Salah ad-Din (Saladin) used it as stables, Napoleon a warehouse and it was later used as a madhouse. Lately it has been restored by an Ismaili Sect from India and as seen it is also used as an impromptu football pitch. Note the 'pepperpot' minaret typical of the period.

The Al-Aqmar (moonlit) mosque was built in 1125 by one of the last Fatimids. It is famous for being the oldest stone facaded mosque in Egypt. Here we see many features which were to become common in later mosques - including the stalactite carving, to be seen either side of the ribbed central hooded arch.

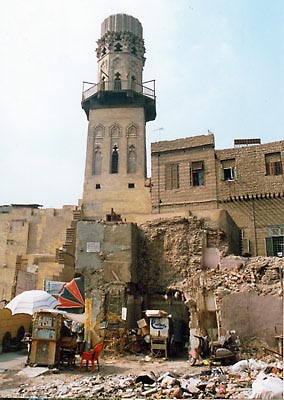

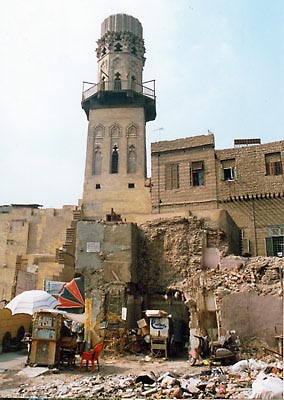

After the Fatimids declined came the Ayyubids (1171 -1250). This was the dynasty of Salah al-Din, the Saladin of western history. He was a Kurd from Syria who subsequently became wazir or prime minister of Egypt before becoming the Khalif of Bagdad and ruling all Arab lands. He subsequently defeated the Crusaders and captured Jerusalem in 1187. Although the madrasa and mausoleum of al-Salih Nagm al-Din Ayyub (1242) are not visible - the minaret is important as it is the only one remaining from the Ayyubid period and shows the transition from the late Fatimid period to early Mamluk. It has three storeys: square, octagonal and a fluted keel-shaped cap. Judging by what is happening around it, it might not last long either.

After the Ayyubids came the Mamluks (1250-1517). Mamluk means slave and they were brought to Egypt as such. Once trained in military arts and Islam they were formally freed. Through ruthlessness, intelligence or merit the young Mamluk officer or amir might hope to advance to the highest offices, even to the sultanate itself. At the sultan's death, rival amirs fought over the succession, often through the streets of Cairo, until the strongest, ablest or most cut-throat prevailed. This period was relatively prosperous for Egypt, being the crossroads of trade and commerce and having a succession of strong rulers. Despite being a violent and bloodthirsty time the Mamluk period also resulted in an amazing number of beautiful buildings.

This double domed complex contains the tombs of the Amir Sayf al-Din Salar and his friend the Amir Alam al-Din Sangar (1303). The adjoining domes although common in northern Syria are unique in Cairo. These domes are brick with stucco ribs which give them the appearance of jelly molds. The minaret is also interesting exhibiting a marked elongation of the top stories and the addition of a circular lantern supporting the mabkhara on top. Note also the stalactite cornices at the top of the six window panels which had become common at the time.

The Madrasa of Sultan Hasan (below left) (1356-1363) is one of the masterpieces of Mamluk architecture in Cairo and one of my favourites. Hasan reigned for fifteen years from when he was thirteen, but was assassinated before the building was completed. Interestingly it remains unfinished in places as some of the panels have been marked out but remain uncarved, almost as if the stone masons finished work one day and did not return. He was not a glorious and impressive sultan but he was able to build such an imposing monument due to the Black Death - the victims' estates were used for royal endowments.

The larger mosque to the right is the Rifa'i Mosque. It is not so well regarded architecturally and is a much more recent mosque finished in 1912. It contains the cenotaph of King Fuad, the last king of Egypt and Shah Pahlevi, the last Shah of Iran.

Here they are again

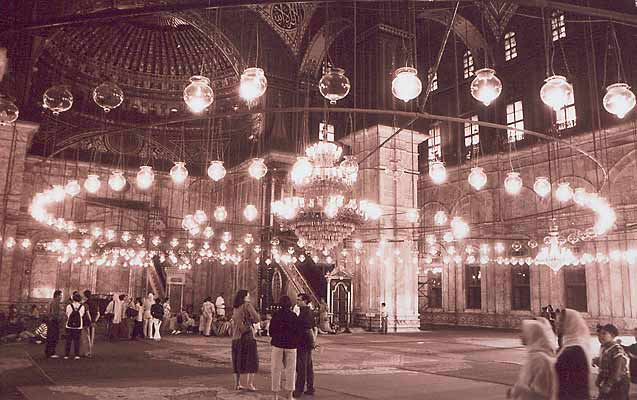

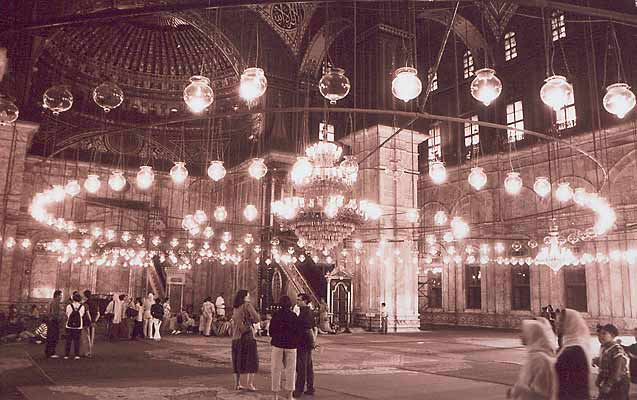

Entering the central courtyard. In the centre of the Sultan Hassan mosque stands a small pavillion originally designed as a decorative fountain but now used for ritual oblutions. Hanging from hundreds of chains are glass oil lamps

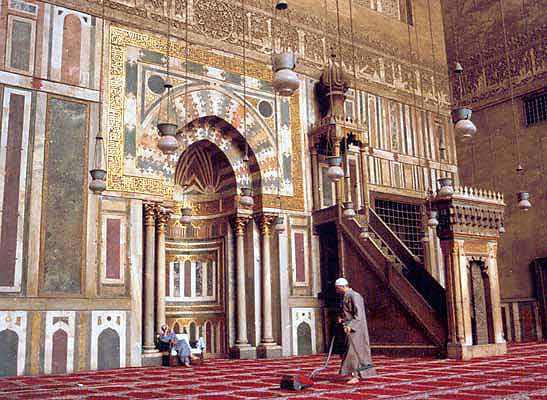

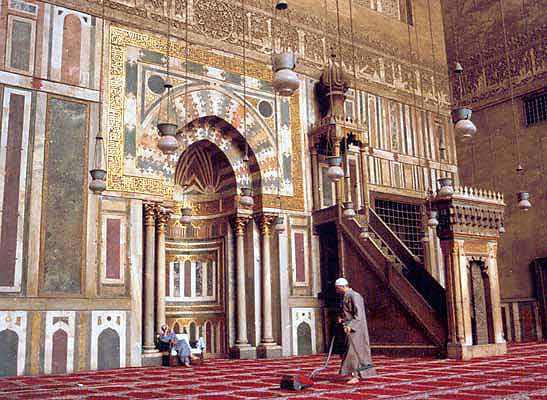

The arched recess is the mihrab and is common to all mosques showing the direction of Mecca. In the top right of the picture, Koranic inscriptions can just be seen and hanging down are mosque lamps. The inlay is marble. To the right is the minbar or pulpit.

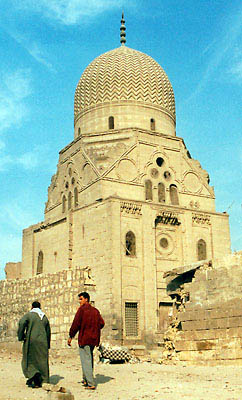

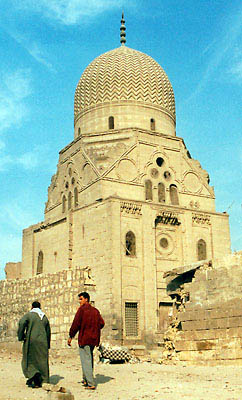

The Madrasa of Ilgay al-Yusufi (1373). A typical Mamluk building with its three storied minaret and stalactite decoration. The twisted ribs of the dome are quite unusual however. In the middle is the The Mausoleum of Yunus al-Dawadar (1382) (Jonah the inkstand holder), the executive secretary who supervised the execution of the sultan's orders. He's not actually buried here as he was killed in battle in Syria but the building is interesting in that the elongated melon-shaped ribbed dome is unique in Cairo but prefigures the Central Asian style associated with the periods of Timur or Tamerlane. On the right is yet another typical minaret from the late Mamluk era.

The following two monuments - the Mausoleum of Tarabay al-Sharifi (1503) (left) and the Mosque of Amir Akhur (1503) (right) represent very late Mamluk architecture with their highly carved domes. Interestingly, the red stripes that can be seen on a number of medieval buildings in Cairo were painted at the behest of Mohammed Ali in the 19th century.

This picture shows the back of Amir Akhur's mosque along with other minarets. It also shows the wall of a house with attractive mashrabiyya windows. These are designed for the women of the house to look out onto the street but remain unseen themselves. They can still be seen on many old houses in Cairo and throughout the Islamic world.

The late Mamluk era became even more violent than before and together with corruption and a ruined economy the regime was ripe for change. That change came with the Ottomans who surged down from Turkey, fuelled by their recent defeat of the Byzantine empire. Under the Ottomans (1517 - 1798), Egypt reverted to the status of a province and underwent a decadent and inglorious period. The Ottomans ruled through a series of viceroys but generally they delegated most of their power to the Mamluks. Architecturally there are many buildings from the Turkish occupation but on the whole are uninspiring and many were badly built. Napoleon invaded Egypt in 1798 and although defeated the medieval army of the Mamluks in the so called battle of the pyramids was unable to hold onto the country. Allied with English seapower the Ottomans drove him out and appointed Mohammed Ali, an Albanian mercenary as their viceroy in Egypt. In 1811 he massacred the leading Mamluks thus ending forever an institution which had survived 550 years. He was to found his own dynasty which lasted until 1952. His reign was notable for the introduction of new Turkish features and styles. His mosque (below) on the citadel is a unique example of a Turkish imperial mosque and by virtue of its dominating site one of the most impressive structures of Cairo.

The Tomb of the Family of Mohammed Ali (1820) is where the three sons of Mohammed Ali lie along with their wives, children, servants and assorted others. The thirty or forty cenotaphs rise in several layers and are exuberantly carved with flowers, garlands and fronds.